Push-Button Cybersecurity: The Dangerous Comfort of Not Knowing How Things Work

A Cognitive Security essay on abstraction, education, and why the cyber workforce gap might be making us less secure.

Section: Cognitive Security | The Pattern Field

In Arthur C. Clarke’s The City and the Stars, humanity lives in Diaspar — a city maintained entirely by machines. No one understands how the city works. No one needs to. The systems are perfect, self-repairing, invisible. The citizens are comfortable, entertained, and completely dependent. It never occurs to them to ask what’s underneath, because underneath has been engineered away.

Clarke wrote that in 1956. He meant it as science fiction.

I think about Diaspar more than I’d like to admit — not because we’ve arrived fully just yet, but because the pattern and trajectory is easily recognizable. We are a civilization increasingly optimized for not knowing how things work. And on almost any given day mostly, that’s fine and to a large extent somewhat inevitable. Abstraction is how complex societies must function. We stand on the shoulders of giants (whether we recognize it or not) precisely so we don’t have to re-derive everything from first principles.

But there’s a question embedded in that comfort: how much can you abstract away before you lose the ability to understand, fix — or importantly — protect — the thing you depend on?

I encounter this question every day. Not in science fiction but the context of a cybersecurity In a cybersecurity classroom.

So an up front confession —

I’ve done the thing I’m about to critique or perhaps to call more attention to. I think most of us in cybersecurity field have. And I think it’s time we talked about it honestly — because the consequences are far reaching and likely only becoming more significant with the advances of AI.

The Growing Push-Button Problem

Here’s a pattern I’ve seen play out across the industry — in training programs, in certification prep, and in young professionals trying to find their way: A student or early-career analyst runs a cybersecurity tool, follows the guide, identifies a suspicious file, and writes it up. Awesome. Outcomes. Clean report. But when you ask “why did you look there?” — silence. When you ask “what is this tool actually doing to the data underneath?” — nothing. They got the answer. They very often have vague notions on how they got to it.

This is push-button cybersecurity. And it’s not the student’s or young professional’s fault.

It’s what happens when an entire industry screaming “we need 500,000 cyber professionals NOW” creates pressure on every part of the pipeline — training vendors, certification bodies, and academic programs alike — to deliver as fast as possible. The incentives push toward throughput. The metric drifts from practitioners developed toward credentials produced. And the tooling makes it easy — richly featured graphical environments, automated scanners, point-and-click cybersecurity — everything designed to hide complexity.

Which is, in most contexts, a feature. In education, it’s a trap.

Perspectives From The “Bridge Generation”

I’m part of what I think of as the bridge generation in tech. We learned from the command line because there was no alternative. We wrote scripts and coded often because nobody had built the tooling yet. We saw the bare metal — the filesystem as a data structure, the network as a series of deliberate decisions, the operating system as a collection of choices someone made that we could inspect, question, and override.

And then we watched the abstraction layers get built on top of all of it.

We saw what came before the shiny tools, and we saw what came after. That gives us a specific kind of understanding — not because we’re smarter, but because we were forced to look at the machinery before someone put a case around it.

Newer students don’t have that experience. And why would they? They’ve grown up in a world where technology works by default. You don’t configure your phone’s filesystem. You don’t think about how a photo gets from the camera sensor to the cloud. Everything just... happens. That’s abstraction doing its job.

But cybersecurity is the one field where you can’t afford to let abstraction do all the work. Because the adversary isn’t constrained by your GUI. A good adversary lives underneath it.

Two Forces, One Problem

I think there are two forces creating this problem, and they’re reinforcing each other.

The first is the cyber workforce gap panic. The headlines are relentless: hundreds of thousands of unfilled positions, critical infrastructure at risk, national security implications. The pressure on educational programs is enormous — produce more skilled professionals, faster. And programs respond rationally: streamline the curriculum, adopt vendor-informed training platforms, standardize on tools that let students reach “competency” in the shortest path possible. None of this is malicious. All of it is incentivized.

The second is abstraction culture — broadly. This isn’t unique to cybersecurity. Few of us really know how our phone fully works. Most software engineers couldn’t explain how a CPU executes their code. We’ve collectively decided that understanding layers below our daily work is someone else’s problem. And that’s mostly fine — until your job is literally to understand how systems fail, how they’re exploited, and how they can be defended at every layer.

When these two forces converge on the cybersecurity pipeline — from training vendors to certification programs to university curricula — the industry risks producing operators and calling them practitioners.

Operators vs. Practitioners

Here’s a distinction I keep coming back to:

An operator knows how to run the tool. They follow procedures. They produce outputs. When the tool works and the situation matches the training, they’re effective. When it doesn’t — when the attack is novel, when the tool throws an unexpected error, when the log format is slightly different from the lab — they stop. They have no foundation to reason from.

A practitioner understands what the tool is doing. They know the assumptions it makes. They know what it’s not showing them. When something unexpected happens, they can reason about it from first principles. They can derive the answer because they understand the system the answer lives in.

The difference shows up immediately in an interviews. Ask someone from a push-button background “how does this tool identify malware?” and they’ll describe the UI workflow. Ask a practitioner the same question and they’ll talk about file signatures, heuristic analysis, entropy measurements, behavioral indicators — the concepts the tool implements. They might not know the exact answer to your specific question, but they can root into a broader knowledge base of how things work and find their way there.

That’s what we should be producing. People who can navigate from fundamentals to solutions — not people who can only navigate from toolbar to output.

Getting Under the Hood

I’ve spent my career on the hands-on side of cybersecurity — most recently as a CISO — and I’ve sat across the interview table from very many who couldn’t explain what their tools were doing. That experience is what interested me in the classroom challenge and experience. In addition to my CISO role, I also teach Cyber Forensics at the esteemed Walker College of Business at Appalachian State University, and that teaching experience and the affordance of flexibility to explore and experiment has only sharpened the questions I’d been carrying from industry. It is those questions that led me to begin White Rabbit — a cybersecurity teaching platform that I’ve been continually developing.

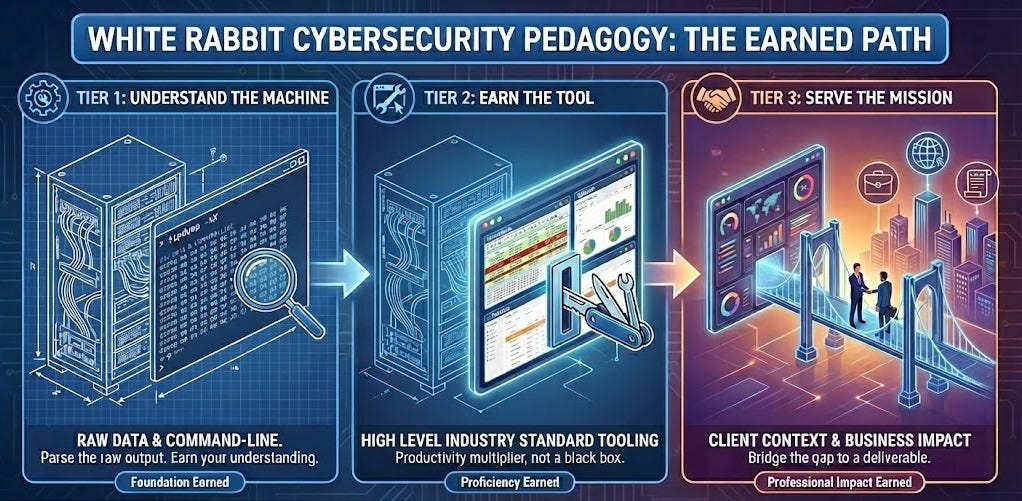

The core pedagogy I’m testing is built around three basic tiers that in a way attempt to replicate those experiences of the bridge generation — meaning each tier is earned, not given:

Tier 1: Understand The Foundation. Before students touch a polished tool, they work with command-line utilities that expose what’s actually happening to the data. They see the raw output. They parse it themselves. They understand what a tool does before they understand what a tool looks like. You earn your understanding before you earn your tools.

Tier 2: Earn the Tool. Then — and this is important — they graduate to the refined tool. We’re not Luddites. The GUI exists for a reason. Efficiency matters. But now when they use it, they’re not trusting a black box. They have a better sense what’s inside it because they’ve already done it the hard way. The shiny tool becomes a productivity multiplier on existing understanding, not a substitute for it.

Tier 3: Connect To The Mission. This is a dimension rarely addressed across the industry’s training landscape: connecting findings to client context. It’s not enough to just identify threat, fix a vulnerability. What does it mean for this organization? What’s the business impact? What do they do next? That’s the gap between a finding and a deliverable — and it’s rarely bridged in the current training landscape.

Standing on the shoulders of giants is how all technology works. Every layer relies on the one below it. I’m not arguing students and journey-level professionals need to understand it all the way down to the transistor. That’s impractical and unnecessary. But there’s a minimum viable depth below which you’re not really a cybersecurity professional — you’re a cybersecurity consumer. And from what I’ve seen on the hiring side — that line is higher than where much of the industry’s training pipeline often ends up.

The Uncomfortable Question

I want to be careful here, because I’m part of this system. I teach in it and I practice within it. I benefit from it. I’m not standing outside throwing stones.

But someone needs to ask: in the rush to close the workforce gap, are we creating a different kind of risk? If we produce thousands of individuals who can operate security tools but can’t reason about security problems — who can follow a playbook but can’t improvise when the playbook doesn’t apply — have we actually made anything more secure?

Or have we just closed the gap on paper?

I don’t have the complete answer. But I know this: every time I watch a student’s face when they finally see what’s happening underneath the GUI — when the abstraction lifts and the actual mechanism is visible — something changes — a mixture of joy and confidence. They go from following to understanding. And they don’t go back.

That moment is what education is supposed to produce. We should be designing for it, not optimizing it away.

And Then... Of Course... There’s AI

Everything I’ve described so far is a problem that was building slowly — through workforce pressure, through abstraction culture, through an industry-wide training pipeline that incentivizes speed over depth. But there’s an accelerant entering the picture that could turn a slow erosion into a collapse.

AI is automating the entry-level work that built practitioners in the first place.

Google’s 2024 report “Secure, Empower, Advance: How AI Can Reverse the Defender’s Dilemma” frames AI as the great equalizer — capable of “empowering existing talent” and helping “new professionals reach the effectiveness of seasoned veterans in a fraction of the time.” The promise is compelling: AI handles the tedious alert triage, log review, and ticket drafting so human analysts can focus on higher-order thinking.

But here’s what I believe that framing misses: those “tedious” tasks were also in a real way the training ground.

Alert triage is how junior analysts learn what normal looks like — so they can recognize abnormal. Log review is how they develop intuition about data flows and system behavior. The repetitive grind of Tier-1 SOC work was never just grunt work. It was the apprenticeship. It was how pattern recognition got built, how instinct got formed, how an operator slowly became a practitioner.

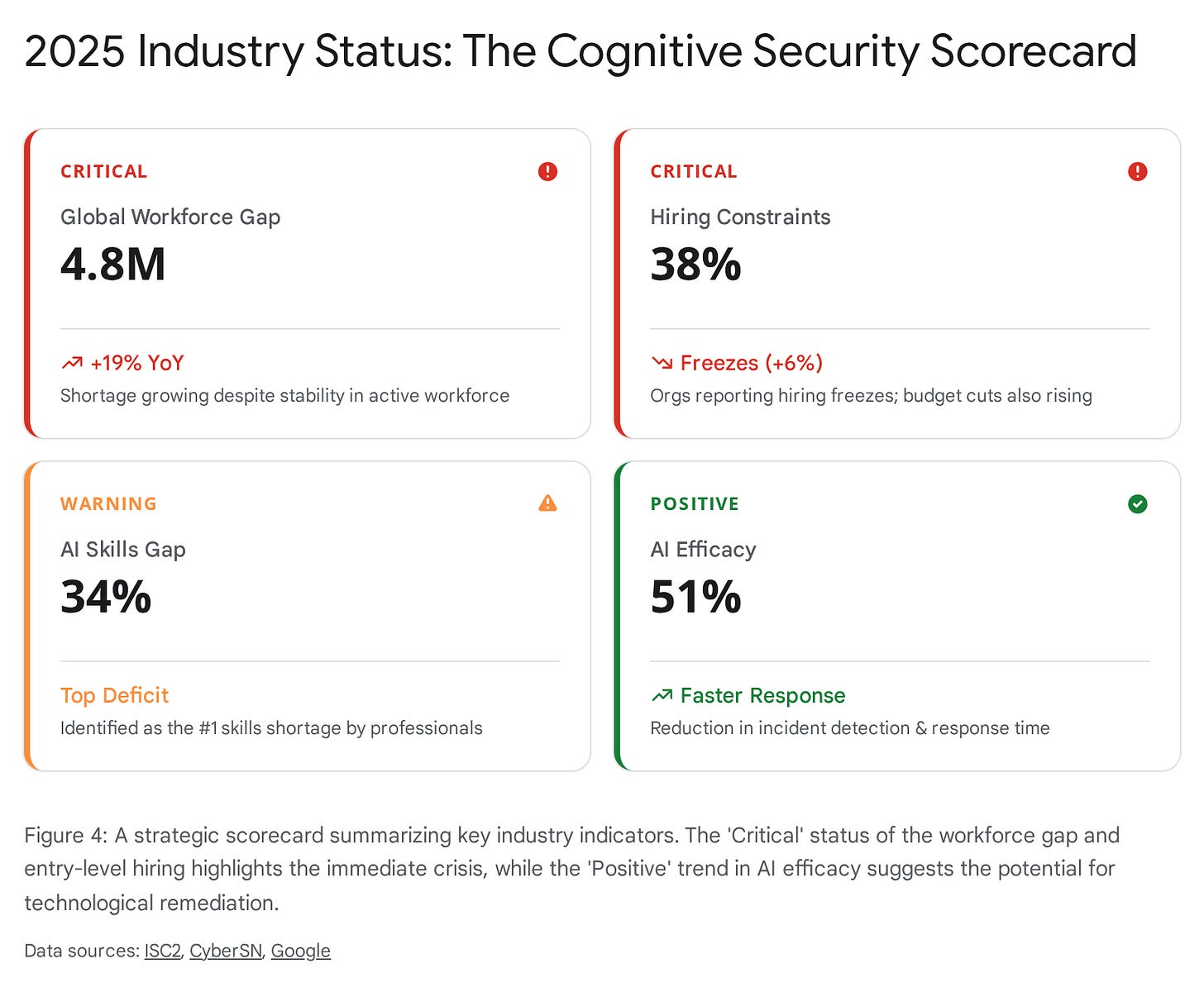

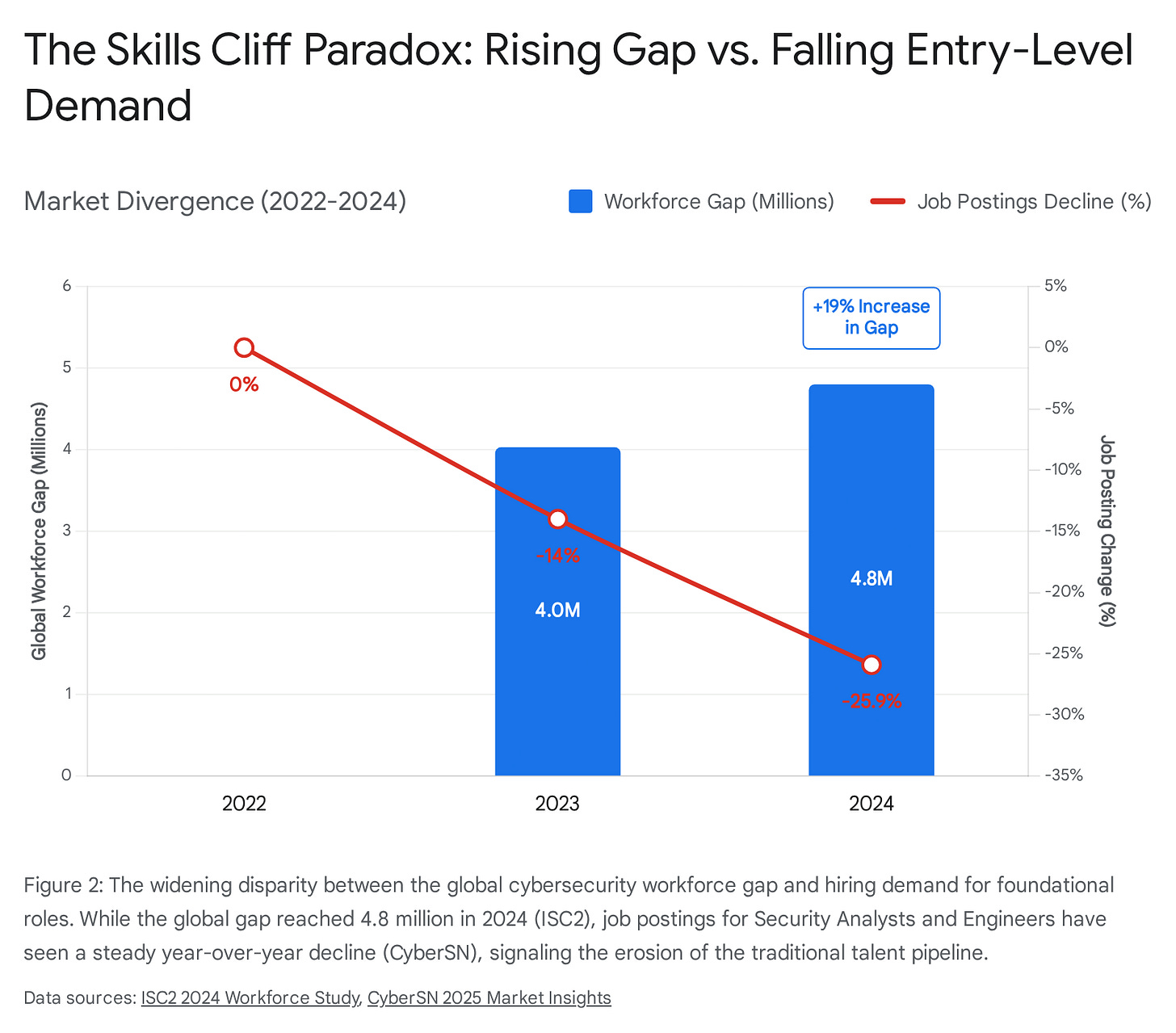

Job postings for security analysts have declined over 25% since 2022, with security engineer roles following a similar trajectory. AI is absorbing the rote work at exactly the moment we need that rote work most — not for its output, but for what it teaches the people doing it and allows them to contextualize important decisions as they rise the ranks. As one industry analysis put it, organizations risk “accelerating efficiency at the cost of developing foundational expertise” — producing a future where leaders lack “the intuitive sense of systems, data flows, and attacker behavior patterns that help senior leaders make quick, grounded decisions in crises.”

This isn’t a skills gap. This is a skills cliff. Or more precisely, it’s a hollow middle — a growing polarization between highly autonomous AI systems on one side and a shrinking cadre of senior human experts on the other, with no clear pathway to bridge the two. The industry is eating its own seed corn: not hiring juniors because AI can do the entry-level work, while failing to recognize that the entry-level work was how juniors became seniors.

The push-button problem I described in the classroom — students who can operate tools but can’t reason about what the tools are doing — that same pattern is about to replicate across the entire industry. And it’s going to happen faster, because AI doesn’t just abstract away complexity. It abstracts away the experience of confronting complexity. The very thing that turns a junior analyst into a senior one.

We now face a convergence: education producing operators instead of practitioners, and AI eliminating the on-the-job training that used to bridge the gap. The senior practitioners who learned the hard way are retiring. The juniors who were supposed to replace them are being trained by tools — in school and now at work — that never require them to understand what’s underneath.

I’m not anti-AI. The defensive applications are real and necessary. But we need to be honest about what we’re trading away in the rush to deploy it. AI should augment practitioners, not replace the very processes that creates them.

Beyond Cybersecurity

I’ve framed this as a cybersecurity problem because that’s where I live. But if you’ve been reading closely, you’ve noticed: this isn’t really about cybersecurity at all.

It’s about the deal we’ve made with abstraction — across every domain, every profession, every layer of modern life. We trade understanding for convenience, depth for speed, and we don’t notice the cost until something breaks and no one in the room knows why.

The mechanic who can only read the diagnostic computer but can’t “listen” to the engine. The doctor who orders the scan but can’t interpret the physical exam. The software engineer who deploys to the cloud but couldn’t sketch the network topology underneath. The citizen who votes but couldn’t explain how the system that counts the vote actually works.

The pattern is everywhere. Cybersecurity just happens to be the domain where the consequences arrive fastest — because someone on the other side is actively looking for the gap between not only what you operate but also critically what you understand.

Carl Sagan saw this coming thirty years ago. In The Demon-Haunted World, he wrote:

“We’ve arranged a global civilization in which most crucial elements profoundly depend on science and technology. We have also arranged things so that almost no one understands science and technology. This is a prescription for disaster. We might get away with it for a while, but sooner or later this combustible mixture of ignorance and power is going to blow up in our faces.”

That was 1995. Before smartphones. Before cloud computing. Before AI wrote code that other AI deployed to infrastructure that no human fully understood. The combustible mixture he described hasn’t dissipated — it’s been enriched.

Clarke imagined Diaspar — a civilization that forgot how its own city worked. Sagan warned that we were building Diaspar, one abstraction layer at a time. Cybersecurity is just the canary in the coal mine — the domain where the gap between operation and understanding has the most immediate consequences.

But the question isn’t really about cybersecurity. It’s about what kind of relationship we want with the systems that run our lives. Passive consumption, or active understanding?

We should be raising people who have a habit of asking: what’s underneath?

This is the first Cognitive Security essay in The Pattern Field — and the beginning of a series on building White Rabbit, a cybersecurity teaching platform designed to bridge the gap between tool operation and deep understanding. I’m building it in public, and learning as I go.

The Pattern Field explores systems at every layer — from the architecture of machines (Cognitive Security), to the architecture of perception (Applied Intuition), to the architecture of meaning (The Source Code). An unusual intersection, deliberately so. Different domains. Same pattern: depth rewards those who pursue it.

If you care about how we train the next generation of cybersecurity professionals — or if you’re just interested in how systems really work beneath the surface — subscribe to follow the journey.

What’s your experience — are we teaching cybersecurity, or are we teaching cybersecurity tools? I’d genuinely like to hear from practitioners, educators, and students in the comments.

James Thomas Webb is a CISO, cybersecurity educator, habitual philosopher, and the occasional builder. He writes The Pattern Field — a newsletter about systems, science, and souls.

Writing Process: I often use AI as a sort of dialectical thinking partner in my writing process — never as a substitute for it. The distinction matters. These are my ideas, tested through conversation.

References

Clarke, Arthur C. The City and the Stars. Frederick Muller Ltd, 1956.

Sagan, Carl. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. Random House, 1995.

Google. “Secure, Empower, Advance: How AI Can Reverse the Defender’s Dilemma.” February 2024.

ISC2. “2024 Cybersecurity Workforce Study.” October 2024. Global cybersecurity workforce gap estimated at 4.8 million; 90% of organizations report skills shortages.

CyberSN. “Insights into the 2025 Cybersecurity Job Market.” Security Analyst postings declined ~26% from 2022-2024; Security Engineer postings declined ~25% in the same period.

SC Media. “Cybersecurity Job Market Faces Disruptions: Hiring Declines in Key Roles Amid Automation and Outsourcing.” Analysis of AI-driven automation reducing demand for entry-level security operations roles.

Dark Reading. “With AI Reshaping Entry-Level Cyber, What Happens to the Security Talent Pipeline?” Examines the risk of AI eliminating the foundational work that develops junior practitioners into senior leaders.

Dropzone AI. “AI Is Automating the SOC, But Can It Train the Next Generation of Analysts?” Discusses how Tier-1 SOC automation removes the apprenticeship pathway for junior analysts.